War and Holocaust

Babyn Yar. Memory and Silence

Execution. Babyn Yar, 1952. Oil on canvas, 35 1/4 x 46 3/8 inches

Untitled, Execution. Babyn Yar series, ca. 1944–52. Oil on canvas, 39 x 51 1/4 inches

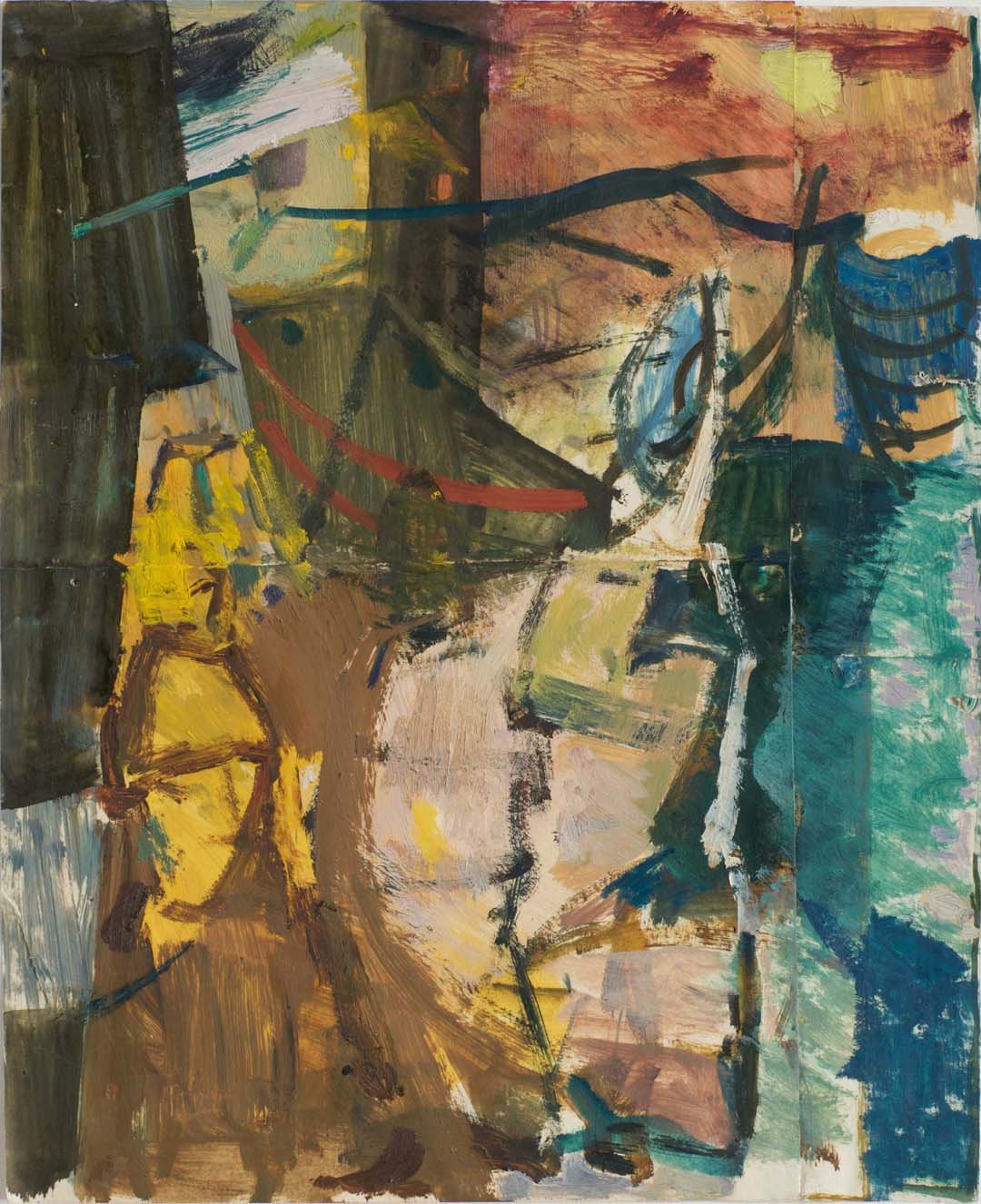

Execution. Babyn Yar series. 1944-52. Oil on paper. 31 1/2 x 42 1/2 inches

Father, Berdichev, mid 1930s. Photo of a painting, whereabouts unknown

Mother, Berdichev, mid 1930s. Photo of a drawing, whereabouts unknown

Brushstrokes of Courage. Bearing Witness to the Holocaust

This presentation is made possible by a digital collaboration between the Havighurst Center of Russian and Post-Soviet Studies at Miami University, the Institute for Russian, European and Eurasian Studies at the University of South Florida, and The Meilkian Center: Russian, Eurasian, and East European Studies at Arizona State University.

Film created by Arivalagan Gajraj, Listen Without Borders

Red Workshop, 1959. Oil on canvas

At the Railway Station. Strelochnitsa, Railway Switcher series. 1961. Oil on canvas

Untitled, from the series Gornoviye, Blast-Furnace Workers (formerly translated as Miners). 1960–63. Gouache and oil on paper

Untitled, ca. 1960s. Pencil on paper

I speak for the dead. We shall rise,

Rattling our bones we’ll go—there,

Where cities, battered but still alive,

Mix bread and perfumes in the air.

—Ilya Ehrenburg, Babi Yar cycle, 1945

Translated from Russian by Maxim D. Shrayer

Untitled, ca. 1950s-60s. Ink on paper

Untitled, ca. 1950s-60s. Ink on paper

Untitled, 1958. Pastel and gouache on paper

Teplushka. Heated Car in the Cargo Train, 1959-1963

The wind carries sand onto enormous common graves. Grass has grown on the fields of death. Tall poplar trees flutter above the earth, like dark flags folded in a sign of mourning.

Vasily Grossman, Ukraine Without Jews, 1943

Evacuation. Refugees, 1961–65. Oil on canvas

Untitled, 1960–65. Pencil on paper

Untitled, 1960–65. Pencil on paper

Composition. Autumn, 1964-1965. Oil on canvas

Study for Autumn, 1962–65. Pencil on paper

Untitled, from the series Evacuation. Refugees, 1963–65. Gouache on paper

As long as humanity has existed on earth, there has never been a murder of innocent and defenceless people as organised, massive, and as cruel as this one. This is the greatest crime ever committed in history, and history has known many crimes; it is written with blood.

Vasily Grossman, Ukraine Without Jews, 1943

Dusk, Matryona’s House, 1960–63. Oil on board

Aunt Katia’s House, Where I Lived, 1960–63. Oil on board

Seamstress. The Siege of Leningrad, 1963–64. Oil on board

THE OLD TEACHER

By Vasily Grossman

short story written in 1943

excerpt

Translated from Russian by Robert and Elizabeth Chandler

When the column of Jews crossed the railway and, leaving the highway, headed off toward the ravine, Haim Kulish the blacksmith took in a lungful of air and, above the hubbub of hundreds of voices shouted in Yiddish, “Oy, friends, I’ve had my day!”

Landing a punch on the temple of the soldier walking beside him, he knocked him down and snatched his submachine gun out of his hands. There was no time to work out what to do with an alien, unfamiliar weapon, and so, just as he had used to swing his hammer, he took a swing with this heavy gun and smashed it into the face of an Unteroffizier who had come running up from one side.

In the commotion that followed, little Katya Weissman lost her mother and her grandmother. She was clutching at the hem of old Rosenthal’s jacket; with some difficulty he picked her up, turned his head to bring his mouth close to her ear, and said, “Don’t cry, Katya, don’t cry!”

Holding on to his neck with one hand, the girl answered, “I’m not crying, teacher.”

It was difficult for him to keep holding her: his head was spinning, his ears were ringing, his legs were shaking from not being used to walking so far, from the agonizing tension of these last hours.

People were backing away from the ravine. Some were refusing to move forward; some were falling to the ground, trying to crawl back. Soon Rosenthal was close to the front of the crowd.

Fifteen men were led to the edge of the ravine. Rosenthal knew some of them: Mendel, the taciturn stove maker; Meyerovich, the dental technician; Apelfeld, that good-natured old rogue of an electrician. Apelfeld’s son was now a teacher in the Kiev Conservatory; when he was a boy, Rosenthal had taught him math. His breathing became labored, but the old man went on holding the little girl in his arms. Thinking about her was a distraction.

“How can I comfort her? How can I deceive her?” the old man wondered, gripped by a feeling of infinite sorrow. At this last minute too, there would be no one to support him, no one to say what he had longed all his life to hear – the words he had desired more than all the wisdom of books about the great thoughts and labors of man.

The little girl turned toward him. Her face was calm; it was the pale face of an adult, a face full of tolerant compassion. And in a sudden silence he heard her voice.

“Teacher,” she said, “don’t look that way, it will frighten you.”

And, like a mother, she covered his eyes with the palms of her hands.

English translation published in Vasily Grossman, The Road, (NYRE Classics, 2010), pp. 113-114

TWO LETTERS TO MOTHER

By Vasily Grossman

Written on the anniversary of her murder by the Nazis during the massacre of Berdychiv, Ukraine, 1941

Translated from Russian by Robert Chandler

excerpts

I have tried dozens, perhaps hundreds, of times to imagine how you died, how you walked to your death. I have tried to imagine the man who killed you. He was the last person to see you. I know that you were thinking about me a great deal – all this time.

—September 1950

It seems to me that my love for you is all the greater, all the more responsible, now that there are so few living hearts in which you still live. I have been thinking of you almost all the time, almost all these last ten years that I have been working; the love and devotion I feel for people is central to this work, and that is why it is dedicated to you.

—September 1961, a year after completing Life and Fate

English translation published in Vasily Grossman, The Road, (NYRB Classics, 2010) pp. 265-266

UKRAINE WITHOUT JEWS

By Vasily Grossman

essay written in 1943

Translated from Russian by Polly Zavadivker

excerpt

Murdered are elderly artisans, well-known masters of trades: tailors, hatmakers, shoemakers. . . . murdered are doctors, therapists, dentists, . . . teachers of history, algebra, trigonometry; . . . murdered are beautiful young women, serious students and happy schoolgirls; . . . murdered are blind people; murdered are deaf and mute people; murdered are violinists and pianists; murdered are three year-old and two-year-old children; murdered are eighty year-old elders who had cataracts in their dimmed eyes, cold transparent fingers and quiet, rustling voices like parchment; murdered are crying newborns who were greedily sucking at their mothers’ breasts until their final moments. . . .

This is the murder of a people, the murder of homes, entire families, books, faith, the murder of the tree of life; this is the death of roots, and not branches or leaves; it is the murder of a people’s body and soul. . .

As long as humanity has existed on earth, there has never been a murder of innocent and defenceless people as organised, massive, and as cruel as this one. This is the greatest crime ever committed in history, and history has known many crimes; it is written with blood.

The Jews of Ukraine are no more.

. . .

Ideological antisemitism is a phenomenon born of a physiological need to explain human and global problems by examining them in a looking glass rather a mirror. . . .

What did the Nazis blame on the Jews? They accused them of the seven deadly sins. The paradoxical, remarkable thing is that the portrait that the Nazis painted of Jews—their supposedly fanatical racism, thirst for global power, hunger to enslave and recklessly rule over humankind—was in fact a self-portrait. By endowing Jews with the traits, flaws and criminal intentions that were raging in their very own hearts, National-Socialism fatefully repeated what previous antisemites had done throughout the ages.

. . .

In gullies and deep ravines, in anti-tank ditches of sand and clay, under heavy black soil, and in swamps and pits, there lie hastily flung bodies of professors and workers, doctors and students, old people and children.

No sound of tears or moaning; no sight of faces drawn from suffering. Jews are silent with the dreadful silence. . . .

The wind carries sand onto enormous common graves. Grass has grown on the fields of death. Tall poplar trees flutter above the earth, like dark flags folded in a sign of mourning.

Silence and peace.

Oh, if the murdered people could be revived for an instant, if the ground above Babi Yar in Kiev or Ostraia Mogila in Voroshilovgrad could be lifted, if a penetrating cry came forth from hundreds and thousands of lips covered in soil, then the Universe would shudder.

***

Introduction to translation of “Ukraine Without Jews”

by Polly Zavadivker

Written soon after the Soviet Army liberated eastern Ukraine from German occupation in mid-1943, the original manuscript of Vasily Grossman’s essay ‘Ukraine Without Jews’ was thought to have been lost after the Second World War. It first appeared in 1990 on the short-lived journal Vek, and is translated here into English for the first time.

‘Ukraine Without Jews’ is a powerful and historically significant essay: one of the earliest public statements about the mass murder of Jews in 1941 and 1942 during the Nazi occupation of Soviet Ukraine, it is also one of the first attempts in any language to systematically explain the ideological and material motives behind the genocide that Grossman calls the ‘greatest crime ever committed in history.’

‘Ukraine Without Jews’ was initially rejected for publication in 1943 by the military newspaper Red Star (Krasnaia Zvezda), where Grossman had earned a huge following from his reports of the Soviet Army’s harrowing defense and stunning victory at Stalingrad. The essay was then translated into Yiddish and published in the weekly paper of the Jewish Anti-Facist Committee, Unity (Einikayt). It was published in two abridged sections and then discontinued. The Yiddish translation remained the only extand version of the essay after 1943, and was back-translated into Russian in 1985. In 1990, the original Russian manuscript (nearly three times the length of the back-translation) surfaced from Grossman’s estate and was published in Vek. . . .

Grossman’s own mother had been among the victims murdered in 1941, in the western Ukrainian city of his birth, Berdichev.

English translation published in Jewish Quarterly, Vol. 58, 2011, Issue 1

BABI YAR

By Ilya Ehrenburg

published in Russian in 1945

Translated from Russian by Maxim D. Shrayer

What use are words and quill pens

When on my heart this rock weighs heavy?

A convict dragging his restraints,

I carry someone else’s memory.

I used to live in cities grand

And love the company of the living,

But now I must dig up graves

In fields and valleys of oblivion.

Now every yar is known to me,

And every yar is home to me.

The hands of this beloved woman

I used to kiss, a long time ago,

Even though when I was with the living

I didn’t even know her.

My darling sweetheart! My red blushes!

My countless family, kith and kin!

I hear you calling me from the ditches,

Your voices reach me from the pits.

I speak for the dead. We shall rise,

Rattling our bones we’ll go—there,

Where cities, battered but still alive,

Mix bread and perfumes in the air.

Blow out the candles. Drop all the flags.

We’ve come to you, not we—but graves.

Note on the text: Originally published as Poem 1 of a cycle of six untitled poems in the leading Moscow monthly Novyi mir (January 1945), Ehrenburg’s poem subsequently appeared, in a modified form, under the title “Babi Yar.”

Copyright © by the Estate of Ilya Ehrenburg.

English translation and note copyright © by Maxim D. Shrayer. All rights reserved